Marching from the Coast to the Capital

One sunny morning last October, several hundred people stood on a dusty field in Makongeni, a Kenyan village near the Indian Ocean. Some of them elderly, they wore red T-shirts written words such as “Ugeni huu mwisho lini?” (Swahili for “When will we stop being treated as visitors?”). Their mission? To become one thing that other people around them are: Kenyan citizens. These were stateless people.

Just two months before, the deadline to register stateless people as citizens had lapsed, but their status was still the same because the government had not completed the process. After decades of distress, the Pemba, Makonde and Rundi communities had had enough. They decided to travel 300 miles, partly on foot, to the president’s residence in the country’s capital Nairobi to seek an audience with him. This was their last, desperate resort in their struggle to be recognized as Kenyans so they could obtain nationality documents to enable them to live normal lives and enjoy the same rights as Kenyans.

A senior government official, Nelson Marwa, asked the stateless people not to embark on the trek because the government would address the problem. They did not buy it. They had waited long enough. Under a blue sky, they said a prayer then set off for Nairobi, accompanied by human rights advocates and with two police vehicles ahead of them to clear the road. The trekkers had nine buses nearby to carry them for some parts of the journey such as places with dangerous wildlife. They planned to complete the walk in three days, spending nights in towns along the way.

A senior government official, Nelson Marwa, asked them not to embark on the trek because the government would address the problem, but they stood firm. Under a blue sky, they said a prayer, then set off for Nairobi, with two police vehicles ahead of them to clear the road. The trekkers had nine buses nearby to carry them for some parts of the journey such as places with dangerous wildlife. They planned to complete the walk in three days, spending nights in towns along the way.

Carrying red placards with messages about their protest, the men and women, some dressed in skullcaps and others in hijabs, marched on the side of the road under the morning sun. They sang and danced in joy while beating drums and blowing whistles. “We all knew we would be granted citizenship,” Shaame Hamisi, a Pemba man who participated in the walk, said in his house in Kwale last December. “We were very happy.”

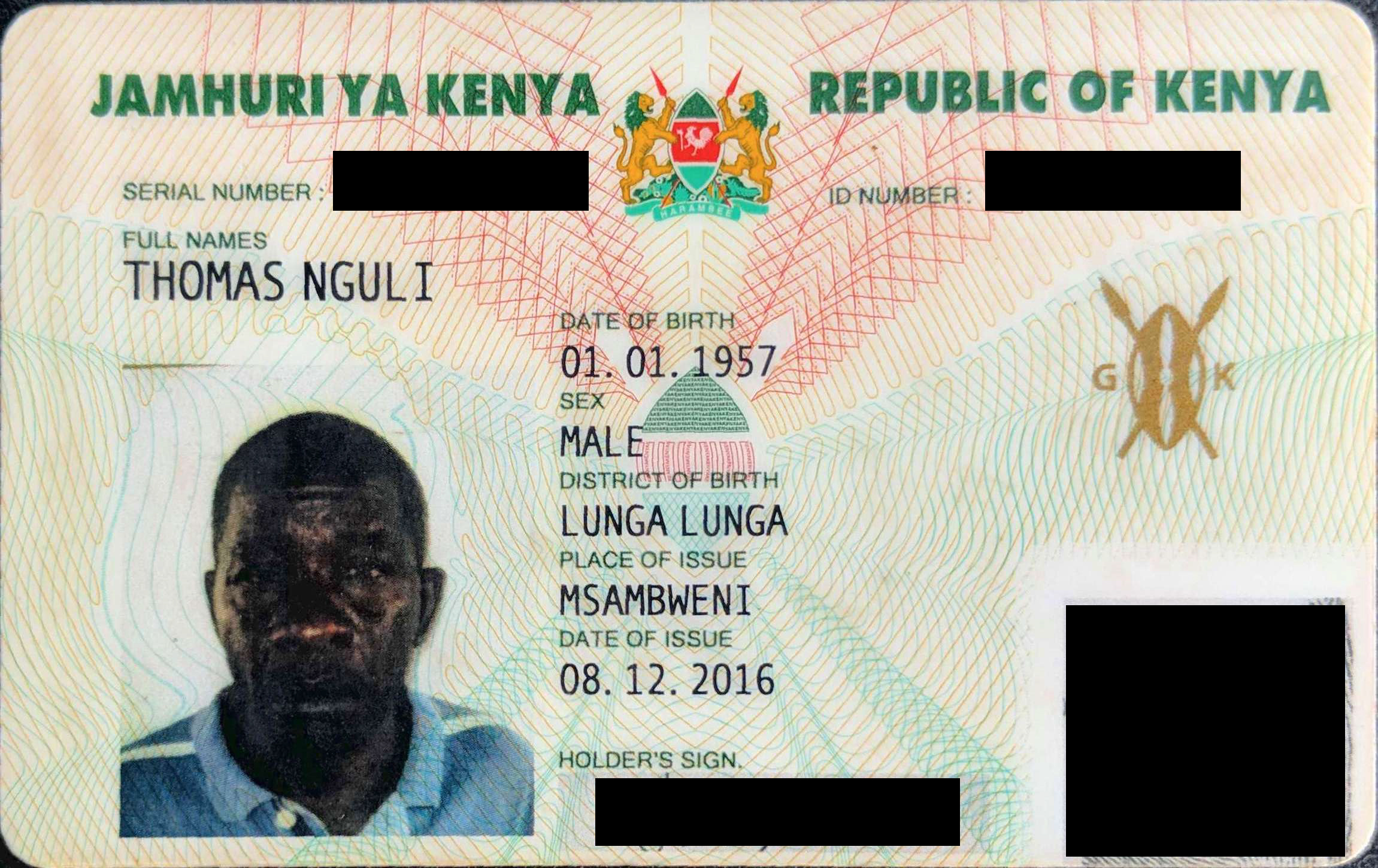

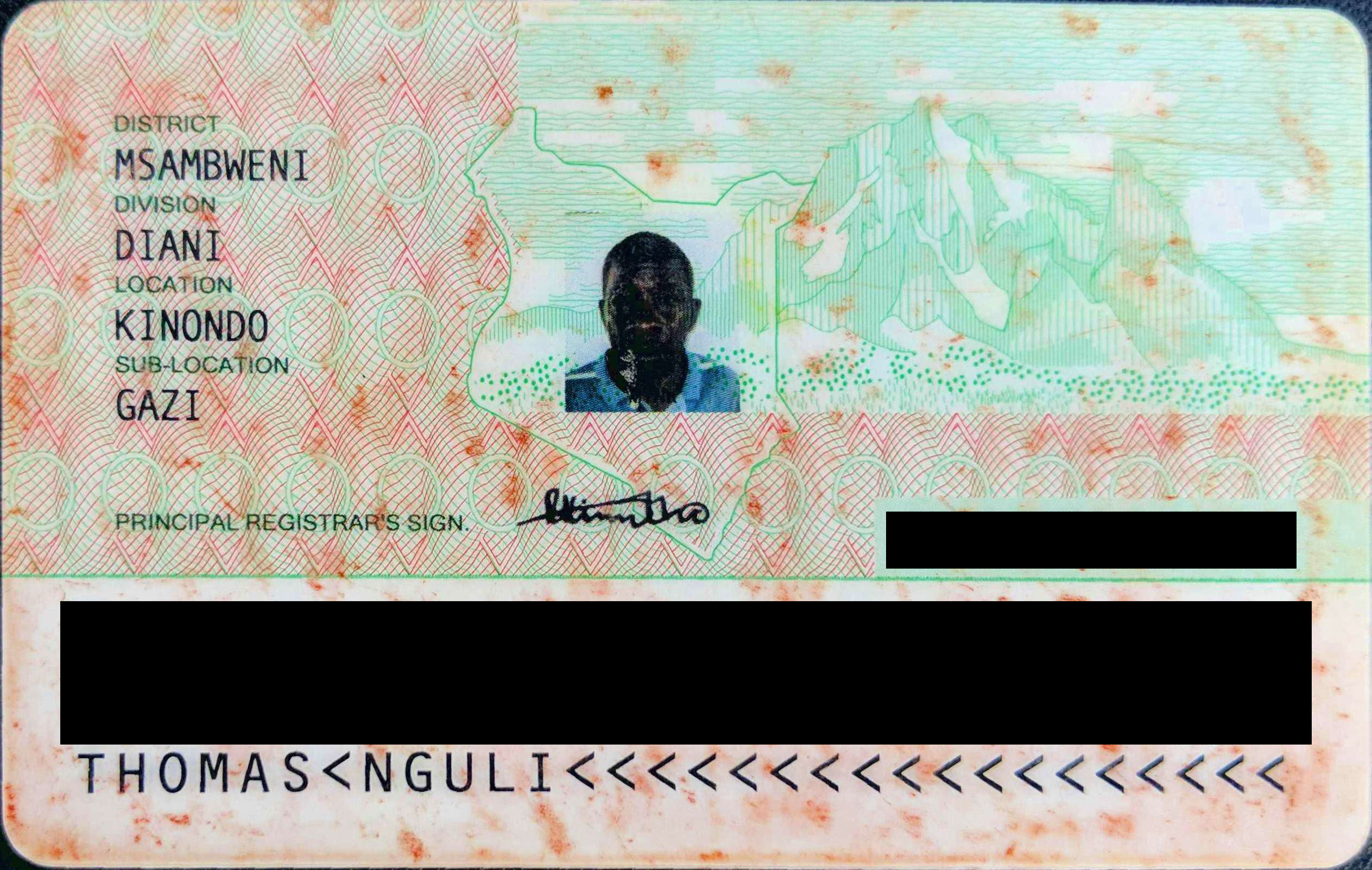

Some 16 miles into the journey, a group of government administrators stopped the procession and asked them to meet with Marwa in a village hall. They refused. Human rights activists had to hide Thomas Nguli, the 60-year-old vocal chairman of the Makonde community, in one of their cars as they feared police would detain him as a strategy to stop the procession. After another? couple of miles, police officers ordered the trekkers to wait for Marwa. He came an hour later and told them the government was addressing their problem and he urged them to abandon their plan.

The statelessness issue would be discussed in the next cabinet meeting, which would probably take place the following week, he said. The stateless people would hear none of this. Nguli, who was the face of the walk, told Marwa officials in the capital had been frustrating their efforts and they had been left with no option but to address the president directly. Marwa allowed them to go, but he threatened to withdraw security. The stateless people were defiant. “We told him, ‘Okay. We are ready to walk because we have no worry,” Nguli says. “If we get harmed, we will just get harmed.” They proceeded with the journey.

When, the following day, they reached Voi, a town one hundred miles from their starting point, police detained them and confiscated their buses for more than two hours at night without an explanation. The trekkers caused a scene, preventing people from accessing services at the police station. The police then let them go.

Three days after leaving Makongeni, the trekkers, weary from their journey, arrived in Nairobi. They walked peacefully to the city center, singing, dancing, chanting and holding up placards, only to be met with the scary sight of anti-riot police and trucks ready to prevent their march to State House, the president’s residence. Nearby stood men in blue uniform wearing helmets and with teargas canisters on their waists and batons in their hands. Nguli and human rights officials squared off against the police officers. Eventually, a senior police officer told the stateless people to go to a nearby park where the security minister, Joseph Nkaissery, would address them.

“You have reached Nairobi. You cannot go back without seeing the president,” Nkaissery told them when he arrived. The president had asked him to come get them and take them to State House, he said. The stateless people were overcome with joy. Mustering whatever energy they had left after the draining walk, they clapped and pumped their fists in the air. Now filled with hope, they boarded their buses and headed to the president’s house in a convoy escorted by police.

In the meeting room with President Uhuru Kenyatta, Nguli and another leader of the Makonde, Amina Kassim, were given a chance to speak. One at a time, they stood in front of a sea of stateless people in red T-shirts and calmly described how they had suffered for decades because of statelessness. The president and other national leaders sat next to a table nearby to their left and listened. “The problem that has made us come here is the national ID,” Nguli said. “For everything you want to do, you need a national ID.”

Then the president, a man with a penchant for making grand promises about tackling national problems, stood up and apologized for the government taking so long to recognize them as Kenyans. He told the security minister and the head of registration to make sure they got national IDs by December. Even before he had finished this last statement, the room exploded with screams of joy. The Makonde started clapping, pumping their fists in the air and shouting in excitement. Some bowed their heads, still on their seats, as if in prayer. There was no mention of the other stateless communities, despite them being in the room and having been part of the convoy. For the Makonde, it was the news they had been waiting for their entire lives. But the Pemba and the Rundi were devastated. “We did not know what to do,” Hamisi said.

In February 2017, President Kenyatta issued the Makonde with national IDs at a ceremony in Kwale. The Pemba, Rundi and other stateless communities in the country remained stateless estimated 18,500 stateless people, “We are just continuing to suffer,” Hamisi says.

In Kenya and other parts of the world, gaps in nationality laws have rendered people stateless, that is, unable to be recognized as citizens of any country. Stateless people are deprived of rights and privileges that citizens of the countries they live in enjoy. They may have difficulty accessing basic rights such as education, healthcare, employment and freedom of movement. Usually, they cannot go to school, see a doctor, get a job, open a bank account, buy a house, move freely or get married legally. People also become stateless because of discriminatory laws, the emergence of new states, changes in borders (like what happened in Cameroon and Nigeria when a ruling by the International Court of Justice demarcated the countries’ border), and the loss or deprivation of nationality. “Statelessness is really a big man-made problem,” says Wanja Munaita, assistant protection officer for statelessness at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Kenya.

Statelessness is a global problem. There are an estimated 12 million stateless people in the world. More than one million of them are the Rohingya from Myanmar in southeast Asia, and an estimated 700,000 live in Ivory Coast in West Africa. More than three quarters of stateless people belong to minority groups. Without proper nationality laws and policies, statelessness will become an ever larger dilemma in the years and decades to come.

Three days after leaving Kwale, the trekkers, weary from their journey, arrived in Nairobi. They walked peacefully on the streets of the city centre, singing, dancing, chanting and holding up placards, only to be met with the scary sight of anti-riot police and trucks ready to prevent their march to State House, the president’s residence. They were men in blue uniform wearing helmets and with teargas canisters on their waists and batons in their hands. After deliberations and confrontation with Nguli and human rights officials, a senior police officer told the trekkers they could not go to State House. He eventually said they should go to a park where the security minister, Joseph Nkaissery, would address them.

“You’ve reached Nairobi. You can’t go back without seeing the president,” Nkaissery told the stateless people in Swahili. The president had asked him to come get them and take them to State House, he said. They stateless people were overcome with joy. Mustering whatever energy they had left after the draining walk, they clapped and pumped fists in the air. Now filled with hope, they boarded their buses and headed to the president’s house in a convoy escorted by police.

At State House, around 200 stateless people and human rights advocates were allowed in while the rest stayed outside. In the meeting room with President Uhuru Kenyatta, a sea of red T-shirts and expectant faces, among the stateless, only representatives of the Makonde community were given a chance to speak: Nguli and the community’s chairperson, Amina Kassim. Then the president gave a speech. He told Nkaissery and the head of registration, Reuben Kimotho, to make sure the Makonde got national IDs by December. There was no mention of the other stateless communities, despite them being in the room and having been part of the convoy.

For the Makonde, it was the news they had been waiting for their entire lives. The Pemba and the Rundi were devastated.

“We did not know what to do,” Shaame Hamisi, a Pemba, said in Swahili in his house in Kwale last December.

The government did not have enough capacity to address statelessness among all the communities in 2016, says Alexander Muteshi, the head of Kenya’s state department for issuance of citizenship.

In February 2017, President Kenyatta issued the Makonde with national IDs at a ceremony in Kwale. The Pemba, Rundi and other stateless communities in the country remained stateless. “We are just continuing to suffer,” Hamisi says.

The Curse of Colonialism Continues

In Kenya, a country that has an estimated 18,500 stateless people, the roots of statelessness go back to the days of British colonialism and laws that discriminated against people who are not indigenous Kenyans. Before colonialism and the drawing of boundaries and the creation of states, Africans were mainly identified by the ethnic groups they belonged to and these communities were not necessarily confined to boundaries, says Prof Hassan Mwakimako of Pwani University in Kilifi, Kenya. They freely moved around for trade and other reasons without official restriction.

But when Kenya got independence in 1963, its new constitution allowed citizenship for people born in Kenya but it also required Kenyan parental heritage. People who had been born in Kenya or were residing there but could not prove their indigenous link to the country were given two years to apply for registration as citizens if they qualified under some conditions. While many people took up this opportunity, mostly those of South Asian descent, not many Africans did, hence becoming stateless and passing their status on to their descendants. The African communities got little information about the registration, Munaita says. She adds that lack of education, and their location far from the capital Nairobi could have also been factors in getting insufficient information.

In Kenya, a country that has an estimated 18,500 stateless people, the roots of statelessness go back to the days of British colonialism and laws that discriminated against people who are not indigenous Kenyans. Before colonialism and the drawing of boundaries and the creation of states, Africans were mainly identified by the ethnic groups they belonged to and these communities were not necessarily confined to boundaries, says Prof Hassan Mwakimako of Pwani University in Kilifi, Kenya. They freely moved around for trade and other reasons without official restriction.

But when Kenya got independence in 1963, its new constitution allowed citizenship for people born in Kenya but it also required Kenyan parental heritage. People who had been born in Kenya or were residing there but could not prove their their indigenous link to the country were given two years to apply for registration as citizens if they qualified under some conditions. While many people took up this opportunity, mostly those of South Asian descent, not many Africans did, hence becoming stateless and passing their status on to their descendants. The African communities got little information about the registration, Munaita says. She adds that lack of education, and their location far from the capital Nairobi could have also been factors in getting insufficient information.

Where Kenya's stateless and formerly stateless came from

Hover over the different paths from countries in East Africa to Kenya to find out where the people of Kenya's different stateless and formerly stateless communities originate.

In 2010, Kenya adopted a new constitution that provided a framework for the registration of stateless people as citizens. This led to creation of a law in 2011 that called for the registration of stateless people within five years – by August 30, 2016. By the end of that five-year window, the government had not registered a single stateless person, leading to the walk that helped the Makonde get citizenship.

A day after the 2016 walk started, the government made a backdated three-year extension of the first deadline – to August 2019.

The process of registering stateless people involves identifying them, doing verification, capturing their biometric data, making recommendations about their registration, and registering them as citizens.

Currently, the state department for issuance of citizenship is focusing on registering four communities that are still stateless: the Pemba, the Rundi, the Shona from Zimbabwe and the people of Rwandan descent, Muteshi says. He acknowledges there are others communities, and says they may consider them based on the results of an ongoing survey on statelessness in the country.

Since 2011, only 1,496 stateless people – the Makonde – have gotten citizenship. The government did not have enough capacity to address statelessness among all the communities in 2016, says Alexander Muteshi, the head of Kenya’s state department for issuance of citizenship. However, he says, the government is now on course and it is banking on an awareness exercise among stateless people and collaboration with other agencies to make the registration a success.

However, judging by the time remaining until August and the estimated 18,500 people yet to be registered as citizens, human rights activists say the government has still not done enough this second time and it is bound to fail meet the deadline once again and there may be need for another deadline extension. “I don't have confidence that all stateless persons in the country will be registered,” Munaita says.

“I don't have confidence that all stateless persons in the country will be registered,” Munaita says.

Stateless People Survive by Living in the Shadows

One hot afternoon in January, Rashid Juma, a 55-year-old stateless man from the Pemba community that is originally from present-day Tanzania, stands gently at a fish shop right next to a road in Watamu, a small coastal town and tourist resort in Kenya’s southeast. In a creamy taqiyah – a Muslim skullcap – grey shorts and brown, dusty open shoes, he is waiting for customers. Just outside the shop, a roughly built structure made of corrugated iron and wood, is Juma’s son, Hassan, a cheeky boy in a blue T-shirt and two wristbands on his left arm. It is a Wednesday, a school day, but Hassan is not in school. Instead, he is swiftly scaling fish and cutting them into pieces at this shop where his father sells fish, amid the noise of tuk-tuks and other vehicles passing by.

Hassan is a little unwell, hence his absence from school today. He is here to learn how his father’s business works because he may end up doing this work himself in some years to come. Hassan is in the eighth grade, the final year of elementary school in Kenya and a stage where you have to take national exams to proceed to high school. One of the requirements to register for these exams is a birth certificate. Like all stateless people in Kenya, Hassan does not have a birth certificate, so he may not do the exam and his education may end at the eighth grade. He cannot get a birth certificate because in applying for one, his parents would have to provide supporting identity documents showing who they are. But as stateless people, they do not have any.

Time is running out for Hassan. The deadline for applying for the national exams is one month away. But rather than watch helplessly as his son gets locked out of education and lives through the same struggles he and five generations of the Pemba have lived in Kenya, Juma, a father of six, has a plan: to use a Kenyan friend’s national ID to get a birth certificate for Hassan. He wants to give the ID to a government official who will then corruptly facilitate having the friend’s name written as Hassan’s father in the document. It is something he has done successfully before for two other children of his, using that same man’s national ID. Juma understands that legally, these children have now become his friend’s, but biologically, they are his. And he is not proud of using this approach.

“I feel very bad because it’s like I’ve given my children to somebody else,” Juma says. “Nobody is pleased when their child has somebody else’s name written as their father’s. Nobody. Because, specifically legally, I’ve given my child to someone else.”

Hassan is disappointed because unlike his fellow schoolmates who are Kenyan and have birth certificates, and will therefore register for the exams, he does not know whether he will do the exams.

“I feel bad because I also want to study, to get a job like other people,” he says. “So that I can improve my life.” But he is aware of his father’s plan and he is hopeful that he will get a birth certificate. Like his father, though, he is not happy they have to use this route. Hassan fears the man whose name would be on the birth certificate may one day claim he is his real father.

The practice of using fake fathers to get birth certificates is a trend among stateless people in Kenya who want their children to become Kenyan citizens. A stateless man or woman who gets a child with a Kenyans partner is lucky though as the Kenyan parent can pass on citizenship to the child, hence they can get a birth certificate.

Where the Pemba lived, before and after colonial rule

Slide the bar in the middle of the two maps to see how control over the 10-mile "Coastal Strip" and the Zanzibar Archipelago changed after Kenya's independence from the British Empire

In a phone call in early April 2019, Hamisi says his plan succeeded, and not just for Hassan, but also for another of his children, Musa, a 13-year-old is in the seventh grade. “I have gotten it,” Hamisi says. “I am grateful.”

The history of how the Pemba ended up in Kenya is a complicated one that is linked to British rule in Kenya and Omani rule in Zanzibar on the Indian Ocean. The Pemba are originally from the eponymous island in the Zanzibar archipelago. They are said to have come to Kenya as early as the 1930s and settled there for fishing. At the time, the part of the coast where the Pemba settled, popularly known as the ten-mile strip, was part of the Sultanate of Zanzibar and therefore under the sovereignty of the Sultan of Zanzibar and not the British. The Pemba were technically in the same territory as Pemba island where they had come from.

This part was officially known as the Protectorate of Kenya. The British ruled inland Kenya and this was known as the Colony of Kenya. As the British ceded sovereignty over inland Kenya for independence in 1963, so did the Sultanate of Zanzibar over the ten-mile strip. Kenya then became a country made of the colony and the protectorate and the Pemba were no longer in the Sultanate of Zanzibar but in the newly formed Kenya. “The Pembas are not indigenous to this area that is confined as the state of Kenya,” says Prof Mwakimako of Pwani University.

Sitting at the rear of a small wooden fishing boat, a grey Yamaha motor behind him and his blue shirt puffing from the wind, Shaame Hamisi holds a string with two very small fish, one on top of the other. We are surrounded by the Indian Ocean. The boat rocks gently in the waves. Behind Hamisi, a tall 56-year-old man with a scruffy beard and a bald head, is Wasini island. “It’s not our fault that we catch such small fish,” Hamisi, who has been fishing for about 30 years, says on the boat.

“It’s because of statelessness. Statelessness is a very annoying thing.”

Hamisi and his two fishing partners are taking us on a short trip to show us how they do their work. It takes a lot of effort and skill for them to catch just one fish, but, after about half an hour and trying a few fishing spots, they succeed. Last night, they fished overnight. Calculating the financial reward of their night-long undertaking later is easy but painful for Hamisi. Fifteen kilograms of fish. That is how much he and his two fellow Pemba fishermen caught together the entire night last night. At a small Swahili restaurant just off the sea on a bright January afternoon, Hamisi, still tired from last night’s work, says one kilo goes for KSh200 ($2). After a long night of fishing, they end up with KSh3,000 ($30). With deductions for renting the fishing boat and for fuel, they are left with about KSh1,000 ($10). Split that among three people. Hamisi has two wives and 14 children.

It is a dog’s life for stateless people in Kenya. They lack access to formal jobs because of their low level of education. They cannot legally do business because they lack the national ID, which is needed to get business permits and licences. This makes it very difficult to support their families financially, and lowering their standard of living.

You need a licence to fish legally in Kenya. So Hamisi and other members of his community are forced to fish near the coastline to avoid being caught by the military, who do patrols further away. Sometimes, the Pemba fish at night, but still near the coastline. But the nearby waters only have small fish. Moreover, without national identity documents, the Pemba cannot buy and register their own fishing boats or get loans to buy them, so they end up renting them from Kenyans, and this reduces their profits.

In Kichaka Mkwaju, a village neighboring Shimoni, sits large swaths of open, almost geometrically shaped areas of sunken light-brown land that are surrounded by trees and bushes. These are quarries. Pemba women, who like their men are locked out of formal jobs because of their low education level, work in these open-pit mines to help support their families. Barefeet, carrying axes and with colorful khangas – traditional Swahili garments – around their waists, they carefully walk down the slopes into a quarry, also crouching and touching the ground to avoid sliding and losing their balance.

Once inside, they get hard at work. And it is back-breaking work. Bending over, some women hit the floor of the quarry hard with their axes to break it into pieces of rock. Another group of then collects the rocks and puts them in plastic buckets and basins. Then another group, lined up in ascension to the top of the quarry, carries the buckets and basins and passes them to each other to the top in a synchronized fashion where the rocks are deposited together.

They sell one 20-litre bucket of rocks for KSh20 ($0.15).

“We mine these rocks, and when we leave here, to be honest, we are really tired,” says Sada Ibrahim, an energetic 50-year-old Pemba woman, at one of the quarries. “Because this work is difficult, and it is difficult! It does not matter if you are a woman or a man.” Ibrahim is holding an ax to her left ear, a khanga wrapped around head and her arms white with dust from showing us how they do the mining. When schools are closed, their children work in the quarries too, to help raise money to buy school uniform.

Shaame Hamisi bought the pieces of land that his two brick houses sit on in Kichaka Mkwaju – one for each of his two families – and he built the houses. He also has a farm. But he cannot legally claim ownership of the property because the ownership documents are in the names of his wives, who are Kenyan. “I don’t have anything,” Hamisi says. Because they lack national identity documents, stateless people in Kenya cannot obtain property ownership documents. Many stateless people are squatters. Some rent houses while others live on land belonging to Kenyan communities on the goodwill of those communities.

Still, they have to rely on the help of Kenyans to get construction permits, to get into tenant agreements and to get their houses connected to utilities such as water, because the processes for these require IDs too. Those who do have property, but do not have Kenyan spouses, may choose to register their property in the names of other Kenyans, friend perhaps, but have the risk of these other people taking the property from them. Phelix Lore, the executive director of a human rights organisation called Haki Centre that does work on statelessness, narrates the story of a stateless man from the Makonde community who married a Kenyan woman and registered a house in her name and had a bank account in her name too. But then one day the wife evicted him from the house, saying he did not belong there, that her “husband” was coming and so he had to leave. The person tried to seek legal advice but he was unsuccessful because he could not prove ownership of the house or the money in the bank.

Even acquiring something as simple as a mobile phone number, a stateless person has to register in another person’s name, because you need a national ID to do this. Kenya is a global leader in mobile money transfer, but stateless people have to be street smart to enjoy this service. When Hamisi receives money in his mobile phone account, he has to ask his wife to take him to withdraw it at an agent shop. Because the number he uses is registered in her name and she therefore needs to produce her national ID in order to get him the money.

“We want to become citizens, so we can get documents, just like the other people,” says Hamisi.

It is Republic Day 2018 in Kenya. At a school playground ground in Ramisi, a small town in Kwale, the local celebration is taking place. Hundreds of local residents are sitting on plastic chairs under tents, listening to speeches and watching performances on one side of the field to celebrate Kenya becoming a republic after gaining independence from Britain. The Kenyan flag flies high on a pole situated on the green between the audience and the speakers and performers, behind them a tent with government officials in uniform. Among the audience are members of current stateless communities – the Pemba, the Rundi and Rwandese people. Nasri Mohamed, a 33-year-old Kenyan man of Pemba descent, is one of them. He has traveled here more than 100 miles from his home in Watamu, Kilifi. Mohamed, a chubby, big-bellied man, is a large-scale fisherman. He is planning a fishing expedition in Lamu, a town 300 miles north of here. For this, he needs other fishermen from the Pemba community. Mohamed has a national ID because his mother is Kenyan.

But the other fishermen he needs for the expedition are stateless. They do not have identity documents. In Kenya, insecurity in some parts of the country means it is sometimes difficult to move from one place to another without some form of identification. There are many security checkpoints, especially in border areas – Kwale borders Tanzania and Lamu borders Somalia – and failure to identify yourself can usually result in arrest. To avoid these checkpoints, some people travel by sea. So besides taking part in the celebration, Mohamed is here to consult Shaame Hamisi, the leader of the Pemba, on how to approach this to ensure the safe return of the people – “because these people have families,” he says. Mohamed has a letter from a local government administrator, a chief, that the other fishermen can present to government officers, police and the military. Because of Lamu’s proximity to Somalia, and the threat of the Shabaab terrorist group, some checkpoints there are manned by soldiers – but he is not sure that the letter is enough to make the fishermen get through the checkpoints.

A month later, we meet Mohamed at a fish shop in his hometown of Watamu. Mohamed owns the shop (He is a citizen and can get a business permit.). Mohamed, in a noticeably oversized white T-shirt with its sleeves past his elbows, tells us he now has more letters from government administrators and the fishermen traveled to Lamu where they are now doing the fishing.

One of the letters, from a deputy county commissioner, lists the names of five fishermen and says: “These are the descendants of the early immigrants from Pemba and are recognized by the government of Kenya only that they are yet to be issued with ID cards and the process is ongoing for them to get the IDs. Their main activity is fishing.... Please assist them where necessary.”

Even traveling long distances in ordinary means is a challenge for stateless people. Many bus companies ask for identification when booking tickets, and for the country’s train and airline services, it is mandatory.

Rashid Juma remembers the exact figure: KSh369,700 ($3,697). Over a few months in 2014, he supplied consignments of fish worth that much to a hotel in Watamu. For payment, the hotel needed a national ID number. Juma did not have one because he is stateless. So he nominated a Kenyan who lived in the same area, and who worked at the hotel to receive the money on his behalf. But the person disappeared with the money and Juma has not seen him since. “I chose him because I trusted him,” Juma says, even though he admits the person was not his friend.

Statelessness causes a lot of financial challenges. Since stateless people cannot open bank accounts, because they lack identity documents, those like Juma who do business with companies that do not pay in cash are forced to have money go through someone else, a risky approach depending on the trustworthiness of the other person. Restriction to banking also means stateless people cannot keep savings in financial institutions or get loans to expand their businesses. Lack of IDs also denies women access to informal cooperative societies known as chamas that offer loans and that are very popular among women in Kenya.

Problems abound, tied to the lack of the all-important identification cards. This forces stateless people to live in the shadows of their Kenyan neighbors.

Kenya has a national healthcare insurance plan but stateless people cannot access it. And recently, according to UNHCR’s Wanja Munaita, there have been two cases of stateless people being detained in public hospitals – in Nairobi and in the central Kenya county of Kiambu – over bills because they were asked to pay higher amounts as “non-Kenyans” since they did not have national IDs. Some stateless people opt to go to more expensive private hospitals instead.

It is also difficult for them to get help in government offices or even enter them because one of the first things officials ask for is an ID to record their details. “It’s not easy,” Juma says. “In fact, we don’t go.”

Perhaps the most personal product of statelessness is ridicule of stateless people by the Kenyan nationals they live with in in their communities – at school and in neighborhoods. There is a feeling among nationals that stateless people are outsiders who do not belong, and when there is conflict between the two groups. It is common to hear comments that the stateless people should go back to “their home.” “It is like they are insulting us,” says Juma, who, like all the other Pemba I spoke to, have never been to the Pemba island.

Sometimes tensions escalate to abuse and get to physical levels, but the Pemba do not bother reporting them to the police because the police would ask them for identification.

“We experience so many challenges, to be honest,” Juma says, “but we are enduring them, because, we do not have anywhere else to go.”

There is a general fear and mistrust of authorities among stateless people. When the government’s statistics body or human rights organizations go out to collect information from them, some stateless people do not come out to participate for fear that they are gathering the information in order to expel them from Kenya. This makes it difficult to know the population of stateless people in the country. Their fear and mistrust is mainly because they suffered a lot of harassment and threats of expulsion by the administration of Kenya’s second president, Daniel arap Moi, and because of continued threats by some local administrators today.

For Those Left Behind, Citizenship isn’t Enough

After the long and tiring march to Nairobi by stateless people in 2016, it took just two weeks for the Makonde to start getting registered for citizenship. They got national IDs and other documents and could finally call Kenya their home.

The Makonde are said to have come to Kenya from Mozambique as early as the 1930s. They were comprised of exiled freedom fighters, refugees fleeing civil war, and laborers recruited by British colonialists to work on sisal and sugarcane plantations in. Life has changed for them in some aspects after gaining citizenship, but in others, not yet.

The Makonde can now study beyond elementary school, legally operate businesses, prove ownership of property, move freely and get affordable healthcare.

Thomas Nguli, the 62-year-old leader of the Makonde and the leader of the 2016 march, walks out of his stony house in Mwabungo village in Kwale on a December afternoon. He is carrying a heavy black and dusty wooden carving and places it on the earth. Brown leaves lie around and tall coconut trees stand nearby.

At about four feet, the carving, made of ebony, is of black shapes of people joined together. Nguli made it over three months it in 2015. He calls it "Family." Carved on its base is his name, Nguli. Historically, the Makonde are known for carving, and Nguli’s carving work, which he has done for about 30 years, has enabled him take care of his family financially – he has one wife and five daughters. He hopes to sell this piece, but he has not done a proper finishing on it yet.

Before he got citizenship, Nguli used to do carving on a local beach but many times authorities would chase him out because of lack of documentation. He would instead use a middleman to sell his work. He would give him a photo of his art to use to look for buyers, for a 10% commission. But now Nguli can sell his work himself, freely.

“I used to pray to God that one day, he would make us live like other people,” Nguli, says later in a classroom in a church compound a short drive from his home. He is also a catechist.

For Makonde youth, the gaining of citizenship gave them a lot of hope that they would now get jobs they could not get before because of the lack of national IDs. But after gaining citizenship, they find that their lack of post-elementary education is now haunting them. For many menial jobs in Kenya, the minimum requirement is a high school certificate. But Makonde youth did not go to high school, and this gives them a huge disadvantage in competing with other Kenyans for jobs. As a result, they have ended up being jobless or doing temporary jobs.

Nguli’s daughter Esther is one such youth. Esther, 22, stands behind her niece Mwanamkasi Musa, who is sitting on a yellow plastic chair. Esther’s fingers quickly and effortlessly move through Musa’s black hair, a bracelet with the Kenyan flag on Esther’s right arm. It is a December morning in the Nguli compound and Esther is putting extensions on her 16-year-old niece’s hair. Esther, who looks four years younger, is a hairdresser. After elementary school, she joined a vocational center to study hairdressing.

Today, she still struggles for employment. Sometimes she gets temporary work at a salon where she gets paid through commissions of 20 or 30%. Other times, like today, she styles people’s hair in their homes. But even these jobs are difficult to come by. “I am trying every way but I cannot see hope,” Esther says. She dreams of opening her own salon.

Esther is a sixth-generation Kenyan Pemba. It is difficult for her generation to improve their living standard, but her son and future generations of the Makonde will have the opportunity to do so by taking advantage of opportunities that statelessness denied the Makonde generations that lived through statelessness.

Indeed, if the Pemba and other people who are still stateless gained citizenship today, it would also take them a long time to catch up with people who have been citizens longer. “They've been left behind. Totally left behind,” Munaita says about the stateless people.

The Long Wait Continues

At the Republic Day celebration, Shaame Hamisi is a little anxious. He comes to the venue a few hours before the event starts with a contingent of fellow Pemba people from Kichaka Mkwaju – old and young, men and women. It is a big day for them. Hamisi, the leader of the Pemba people, has been officially invited to this national function. He has also been given an opportunity to speak to the hundreds of attendants and, importantly, the government officials present. The Pemba people have come early to rehearse their songs and dances because they are also set to perform at the event.

When Hamisi’s turn to speak comes, he cuts a sad and emotional figure. Holding a microphone on his right arm and standing right in front of three seated government administrators in their well pressed, shiny khaki uniform, he gives an impassioned speech, crying for his people to be granted citizenship.

Kenyan citizens have two things to celebrate today, he says – Kenya becoming a republic and them being citizens – but the Pemba are only celebrating Kenya becoming a republic. “We have a lot of sadness,” he says. “Until now we still have not been lucky enough to get citizenship yet we are real Kenyans.”

Kenya still has some time to make the Pemba and other stateless people in the country citizens before the August 30 deadline. Doing so largely depends on the speed and commitment of the Directorate of Immigration and Registration of Persons. “The process is not an easy process,” says Alexander Muteshi, Kenya’s director of the immigration services. “And that's why you see it has taken quite long.” He notes that lack of enough data about stateless communities is a major challenge.

For now, Hamisi and other stateless people in Kenya continue to wait and hope for the day they will finally get recognition in a country they have lived their entire lives but that still treats them as strangers. They have become accustomed to feeling they do not belong in Kenya. They live and die without legal records of their identities, as if they have never existed, and without the chance to fulfil their potential because of lack of documentation.

“Sometimes you wonder why you were brought into this world,” Hamisi says. “‘Why? What did I come to do here?’ You think it would even be better then for God to get you out of this world.”